Top Organizational Tips for the Whirlwind Writer

I carry a notebook with me where ever I go. I keep an extra

one in the car in case I’ve forget the other, have sharpies scattered

everywhere in case the notebooks fail and will resort to napkins and the back

of business cards like the best of them.

Over the years, I’ve wasted a lot of time sorting through

that crap.

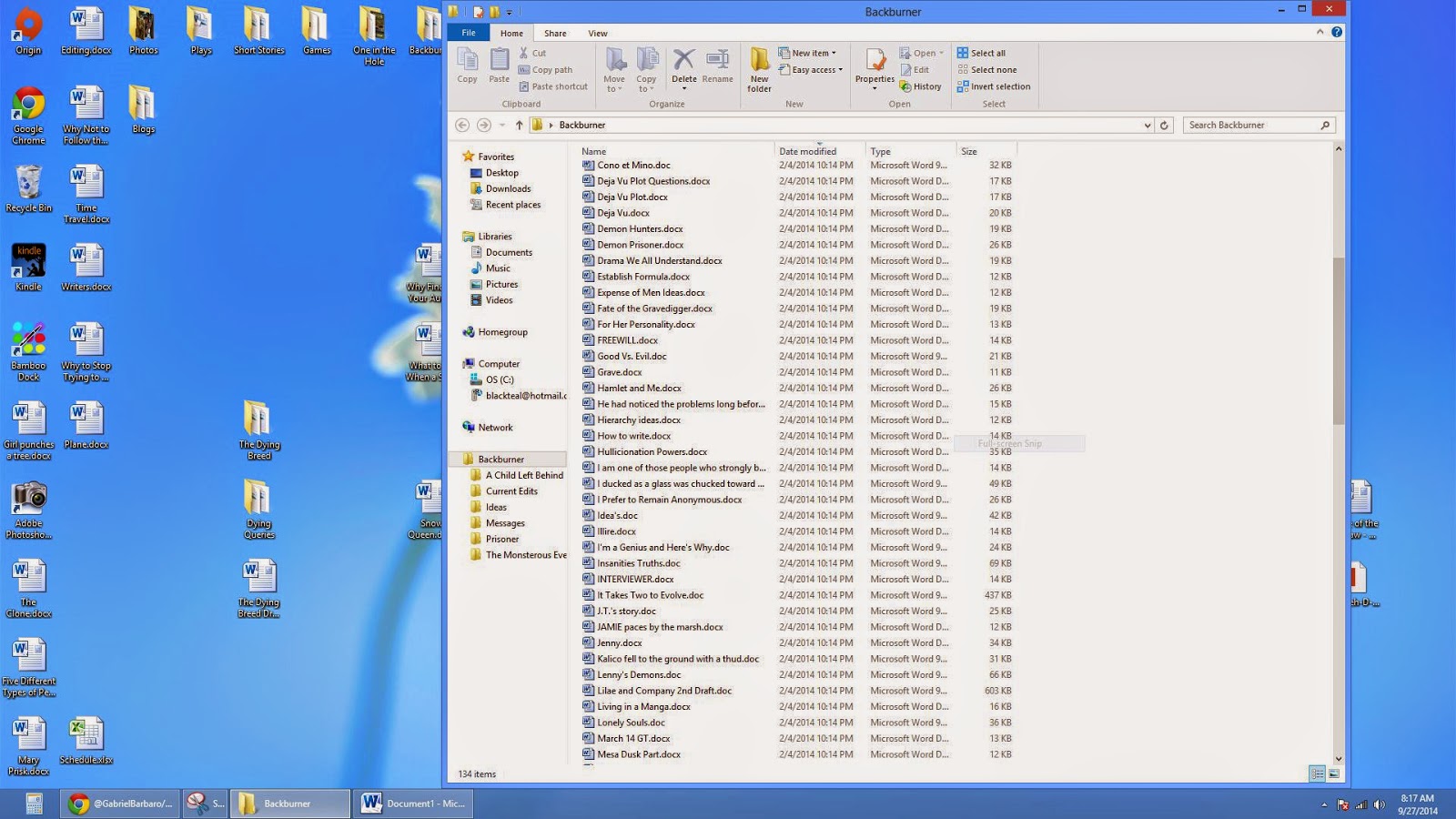

1. Name every story.

I think everyone past the age of ten has learned why naming

documents “kjdsjkdohjioajdioj,” is a bad idea, but many writers, when first

starting out, still call their books “Untitled,” or “Story” or “Book.” Or, with

Word’s newest features, whatever the first few lines in the document are… So a

lot of “Chapter One”s.

If you haven’t started fifty-thousand stories, this isn’t

really a problem. And most people truly believe that they’ll only work on this

one book, or they’ll remember the difference between Untitled 1 and Untitled

5,392. And some people will.

However, there’s two reasons why having a specific working

title is a good idea. One, on topic, is simple organization. If you start

finding yourself with more than two books started, it is a quick way to “file” them,

and to find one when you need it.

I personally have found that stopping mid-manuscript to

start another I’m currently inspired about works very well for me—but that’s

because I write every day. I have a lot of beginnings or middles or ends that I

wrote when I was excited about them, then went back to my current. What ends up

happening is that I now have all of these ideas I can easily start when the

current is finished, or scenes that I can merge and use to develop other ideas.

Problem is, I need a quick way to find them. Just by naming them some simple

word that cues my memory, I can scan through my fiction file and remember every

single story without having to open it, even years after I wrote it.

And the other, off topic, reason is that it’s important to

“test out” titles as you write instead of just waiting for the perfect one to

smack you in the face. By giving the book various labels and using them in

context, you are more equipped to know if you like one or not, and setting up

your mind to give you one of those shower epiphanies.

2. Label every non sequitur

page.

If you’re the sort of person who writes longhand first in

the same notebook without any doodles or deviations from that story, then this

is unnecessary. But if you are anything like me and your notebooks seem more

like the rambling tangents of a madman—containing nonrelated images and all

different sections from completely different novels—this is the most useful labeling

that took me seven years to figure out.

I label each page or business card with four things: Working

title, date, page numbers of that scene in the notebook, and where I’d last

written a part of that same novel. And, very importantly, if I don’t remember

the last words I’d written elsewhere, I’ll add (Skip), which will tell me that

it’s not going to line up with each other, and I’m going to need to add a

transition.

It looks like this:

The Dying Breed: Sept. 28, 2014 pg. 1 (Doc).

Now if I was a good writer and went straight home to type up

my pages, I’d remember long enough for this to be ridiculous. But seeing how I

can wait weeks, months, and, yes, even sometimes years, this has been an

efficient method of not losing sections, and not having to read a bunch to know

if this section is the right section or not.

I’ll often just skip over the already written section and

keep writing. Then, as the book nears its end, I’ll finally go back and try to

fill in the blanks.

The title not only tells me that “This is an actual story

section and not just notes,” (or even sometimes basic rambling if I’m really

bored), but that “This is the story you are looking for.” The date also tells

me if I should bother reading something. If what was written on April 10th

has already been typed and happened before the missing section, then it is

unlikely that what was written on April 5th will be what I’m looking

for.

Page numbers do what page numbers do. And telling me where I

last wrote lets me know if I have a full section before me. Sometimes

transitions from what was last in the document to what is first in the notebook

don’t make a lot of sense, and it’s a quick way to know if that’s because I’m

missing a part, or because I just didn’t remember exactly what I last wrote.

3. Cross out all typed up

pages.

This one’s simple. You may think you’ll remember typing

something up, but you don’t. Be diligent about marking pages that you’ve

already typed, otherwise, You’ll have to read through it. Sometimes Finder works,

typing the first few words in the search bar, but a lot of times there will be

a slight change, and you won’t be able to find it. (Especially due to the

transition issue.)

4. Have one box for all non

sequitur pages and notebooks.

Get an inbox. When you get home from a long day of ignoring

your boss and writing instead of taking notes, take those pages and put them in

that box. When you fill up a notebook—unless you know everything inside has

been typed—put that in that box.

What this does is make sure that if you can’t find it, you’ve

definitely lost it.

I can’t tell you how much stalling I have done because I

may-have, may-have-not, lost a section and need to rewrite it. Rewriting a

section—especially after having gone on with scenes continuing it—can be a

really painful experience. You’ll never get it exactly the same, and one word

can change a character from understanding to being horribly pissed.

It doesn’t seem important when you believe you’ll be typing

it up soon, but I definitely got to a point in which anyone throwing out a

piece of paper sends me into a incapacitating panic. Including myself.

Now that I have my inbox and keep all my filled notebooks in

one spot, I have a limited place to look, and I don’t have to worry about

chucking random post-its.

5. Know Thyself.

Okay, so this one is kind of a cop out, but I’ll say that I

have plenty of cop outs, and many of them are better. I use, “Know thyself,”

because it is not only vague enough

to be true, but because it is actually the most useful.

The fact is that it took me years to learn how I work,

procrastinate, and how to protect myself from crying over milk spilling across

my napkin and smearing the words. Metaphorically, of course. You can’t prevent

that shit. When I started to understand how my laziness affected my

effectiveness, that’s when I stopped losing pages, stopped allowing frustration

to win over inspiration, and stopped spending so much time rereading my

scribbles in hopes to find what I need.

While many of these tips will not work for some and be just

a complete waste of time for others, the point is that if I just accepted that I would probably not go straight home and get

the damn thing on the computer, that I tended to lose stuff, and very often worked

on sixteen projects at once, then I could have easily saved myself the headache

by organizing myself much earlier in my career.

If you take a look at my room, my car, or anywhere I’ve been

for five minutes, you’ll know that I shun organization like the best of them. I

just see a huge difference in how important finding your writing is over your

car keys.